This, according to Wikipedia:

Anarchy is the condition of a society, entity, group of persons or single person which does not recognize authority.

[1] It originally meant leaderlessness or lawlessness, but in 1840,

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon adopted the term in his treatise

What Is Property? to refer to a new

political philosophy,

anarchism, which advocates stateless societies based on

voluntary associations.

Etymology

The word

anarchy comes from the

ancient Greek ἀναρχία (

anarchia), which combines

ἀ (

a), "not, without" and

ἀρχή (

arkhi), "ruler, leader, authority." Thus, the term refers to a person or society "without rulers" or "without leaders."

[2]

Anarchy and political philosophy

Kant on anarchy

The German philosopher

Immanuel Kant treated anarchy in his

Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View as consisting of "Law and Freedom without Force". Thus, for Kant, anarchy falls short of being a true

civil state

because the law is only an "empty recommendation" if force is not

included to make this law efficacious. For there to be such a state,

force must be included while law and freedom are maintained, a state

which Kant calls

republic.

[3][4]

As summary Kant named four kinds of government:

- Law and freedom without force (anarchy).

- Law and force without freedom (despotism).

- Force without freedom and law (barbarism).

- Force with freedom and law (republic).

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the

political philosophy which holds the state to be

immoral,

[5][6] or alternatively as opposing

authority in the conduct of human relations.

[7][8][9][10][11][12] Proponents of anarchism, i.e. anarchists, advocate

stateless societies based on what are sometimes defined as non-

hierarchical organizations,

[7][13][14] and at other times defined as

voluntary associations.

[15][16]

There are many types and traditions of anarchism, not all of which are mutually exclusive.

[17] Anarchist schools of thought can differ fundamentally, supporting anything from extreme individualism to complete collectivism.

[6] Strains of anarchism have been divided into the categories of

social and

individualist anarchism or similar dual classifications.

[18][19] Anarchism is often considered to be a radical

left-wing ideology,

[20][21] and much of

anarchist economics and

anarchist legal philosophy reflect

anti-statist interpretations of

communism,

collectivism,

syndicalism or

participatory economics.

"To see this, of course, we must expound the moral outlook underlying

anarchism. To do this we must first make an important distinction

between two general options in anarchist theory [...] The two are what

we may call, respectively, the socialist versus the free-market, or

capitalist, versions."

[22] Some individualist anarchists are also

socialists or

communists while some anarcho-communists are also individualists

[23][24] or egoists.

[25][26]

Anarchism as a

social movement

has regularly endured fluctuations in popularity. The central tendency

of anarchism as a mass social movement has been represented by

anarcho-communism and

anarcho-syndicalism, with

individualist anarchism being primarily a literary phenomenon

[27] which nevertheless did have an impact on the bigger currents

[28] and individualists also participated in large anarchist organizations.

[29][30] Most anarchists

oppose all forms of aggression, supporting

self-defense or

non-violence (

anarcho-pacifism),

[31][32] while others have supported the use of

militant measures, including

revolution and

propaganda of the deed, on the path to an anarchist society.

[33]

Since the 1890s, the term

libertarianism has been used as a synonym for anarchism

[34][35] and was used almost exclusively in this sense until the 1950s in the United States. At this time,

classical liberals

in the United States began to describe themselves as libertarians, and

it has since become necessary to distinguish their individualist and

capitalist philosophy from socialist anarchism. Thus, the former is

often referred to as

right-wing libertarianism, or simply

right-libertarianism, whereas the latter is described by the terms

libertarian socialism,

socialist libertarianism,

left-libertarianism, and

left-anarchism.

[36][37] Right-libertarians are divided into

minarchists and anarchists, with the latter often described as

libertarian anarchists.

[38][39] Outside the United States,

libertarianism generally retains its association with left-wing anarchism.

[40]

Anarchy and anthropology

Some anarchist anthropologists, such as

David Graeber and

Pierre Clastres, consider societies such as those of the

Bushmen,

Tiv and the

Piaroa to be anarchies in the sense that they explicitly reject the idea of centralized political authority.

[41]

Other anthropologists, such as

Marshall Sahlins and

Richard Borshay Lee,

have repudiated the idea of hunter-gatherer societies being a source of

scarcity and brutalization; describing them as "affluent societies".

[42]

The

evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker writes:

Adjudication by an armed authority appears to be the most effective

violence-reduction technique ever invented. Though we debate whether

tweaks in criminal policy, such as executing murderers versus locking

them up for life, can reduce violence by a few percentage points, there

can be no debate on the massive effects of having a criminal justice

system as opposed to living in anarchy. The shockingly high homicide

rates of pre-state societies, with 10 to 60 percent of the men dying at

the hands of other men, provide one kind of evidence. Another is the

emergence of a violent culture of honor in just about any corner of the

world that is beyond the reach of law. ..The generalization that anarchy

in the sense of a lack of government leads to anarchy in the sense of

violent chaos may seem banal, but it is often over-looked in today's

still-romantic climate.[43]

Some

anarcho-primitivists

believe that this concept is used to justify the values of modern

industrial society and move individuals further from their natural

habitat and natural needs.

[44][45] John Zerzan has noted the existence of tribal societies with less violence than "advanced" societies.

[46] Zerzan and

Theodore Kaczynski

have talked about other forms of violence against the individual in

advanced societies, generally expressed by the term "social anomie",

that result from the system of monopolized security.

[47] These authors do not dismiss the fact that humanity is changing while adapting to its different social realities,

[48]

but consider the situation anomalous. The two results are (1) that we

either disappear or (2) become something very different from what we

have come to value in our nature. It has been suggested that this shift

towards civilization, through domestication, has caused an increase in

diseases, labor, and psychological disorders.

[49][50][51] In contrast,

Pierre Clastres

maintains that violence in primitive societies is a natural way for

each community to maintain its political independence, while dismissing

the state as a natural outcome of the evolution of human societies.

[52]

Examples of state-collapse anarchy

English Civil War

Anarchy was one of the issues at the

Putney Debates of 1647:

- Thomas Rainsborough:

I shall now be a little more free and open with you than I was before. I

wish we were all true-hearted, and that we did all carry ourselves with

integrity. If I did mistrust you I would not use such asseverations. I

think it doth go on mistrust, and things are thought too readily matters

of reflection, that were never intended. For my part, as I think, you

forgot something that was in my speech, and you do not only yourselves

believe that some men believe that the government is never correct, but

you hate all men that believe that. And, sir, to say because a man

pleads that every man hath a voice by right of nature, that therefore it

destroys by the same argument all property -- this is to forget the Law

of God. That there’s a property, the Law of God says it; else why hath

God made that law, Thou shalt not steal? I am a poor man, therefore I

must be oppressed: if I have no interest in the kingdom, I must suffer

by all their laws be they right or wrong. Nay thus: a gentleman lives in

a country and hath three or four lordships, as some men have (God knows

how they got them); and when a Parliament is called he must be a

Parliament-man; and it may be he sees some poor men, they live near this

man, he can crush them -- I have known an invasion to make sure he hath

turned the poor men out of doors; and I would fain know whether the

potency of rich men do not this, and so keep them under the greatest

tyranny that was ever thought of in the world. And therefore I think

that to that it is fully answered: God hath set down that thing as to

propriety with this law of his, Thou shalt not steal. And for my part I

am against any such thought, and, as for yourselves, I wish you would

not make the world believe that we are for anarchy.

- Oliver Cromwell:

I know nothing but this, that they that are the most yielding have the

greatest wisdom; but really, sir, this is not right as it should be. No

man says that you have a mind to anarchy, but that the consequence of

this rule tends to anarchy, must end in anarchy; for where is there any

bound or limit set if you take away this limit , that men that have no

interest but the interest of breathing shall have no voice in elections?

Therefore I am confident on 't, we should not be so hot one with

another.[53]

As people began to theorize about the English Civil War, "anarchy"

came to be more sharply defined, albeit from differing political

perspectives:

- 1651 – Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan) describes the natural condition of mankind as a war of all against all,

where man lives a brutish existence. "For the savage people in many

places of America, except the government of small families, the concord

whereof dependeth on natural lust, have no government at all, and live

at this day in that brutish manner."[54] Hobbes finds three basic causes of the conflict in this state of nature:

competition, diffidence and glory, "The first maketh men invade for

gain; the second, for safety; and the third, for reputation". His first law of nature

is that "every man ought to endeavour peace, as far as he has hope of

obtaining it; and when he cannot obtain it, that he may seek and use all

helps and advantages of war". In the state of nature, "every man has a

right to every thing, even to then go for one another's body" but the

second law is that, in order to secure the advantages of peace, "that a

man be willing, when others are so too… to lay down this right to all

things; and be contented with so much liberty

against other men as he would allow other men against himself". This is

the beginning of contracts/covenants; performing of which is the third

law of nature. "Injustice," therefore, is failure to perform in a

covenant; all else is just.

- 1656 – James Harrington (The Commonwealth of Oceana) uses the term to describe a situation where the people use force to impose a government on an economic base composed of either solitary land ownership (absolute monarchy), or land in the ownership of a few (mixed monarchy). He distinguishes it from commonwealth,

the situation when both land ownership and governance shared by the

population at large, seeing it as a temporary situation arising from an

imbalance between the form of government and the form of property

relations.

French Revolution

Heads of Aristocrats, on spikes

Thomas Carlyle, Scottish essayist of the Victorian era known foremost for his widely influential work of history,

The French Revolution, wrote that the French Revolution was a war against both

aristocracy and anarchy:

Meanwhile, we will hate Anarchy as Death, which it is; and the things

worse than Anarchy shall be hated more! Surely Peace alone is fruitful.

Anarchy is destruction: a burning up, say, of Shams and

Insupportabilities; but which leaves Vacancy behind. Know this also,

that out of a world of Unwise nothing but an Unwisdom can be made.

Arrange it, Constitution-build it, sift it through Ballot-Boxes as thou

wilt, it is and remains an Unwisdom,-- the new prey of new quacks and

unclean things, the latter end of it slightly better than the beginning.

Who can bring a wise thing out of men unwise? Not one. And so Vacancy

and general Abolition having come for this France, what can Anarchy do

more? Let there be Order, were it under the Soldier's Sword; let there

be Peace, that the bounty of the Heavens be not spilt; that what of

Wisdom they do send us bring fruit in its season!-- It remains to be

seen how the quellers of Sansculottism were themselves quelled, and

sacred right of Insurrection was blown away by gunpowder: wherewith this

singular eventful History called French Revolution ends.[55]

Armand II, duke of Aiguillon came before the

National Assembly in 1789 and shared his views on the anarchy:

I may be permitted here to express my personal opinion. I shall no

doubt not be accused of not loving liberty, but I know that not all

movements of peoples lead to liberty. But I know that great anarchy

quickly leads to great exhaustion and that despotism, which is a kind of

rest, has almost always been the necessary result of great anarchy. It

is therefore much more important than we think to end the disorder under

which we suffer. If we can achieve this only through the use of force

by authorities, then it would be thoughtless to keep refraining from

using such force.[56]

Armand II was later exiled because he was viewed as being opposed to the revolution's violent tactics.

Professor Chris Bossche commented on the role of anarchy in the revolution:

In The French Revolution, the narrative of increasing anarchy

undermined the narrative in which the revolutionaries were striving to

create a new social order by writing a constitution.[57]

Jamaica 1720

Sir

Nicholas Lawes, Governor of

Jamaica, wrote to

John Robinson, the

Bishop of London, in 1720:

- "As to the Englishmen that came as mechanics hither, very young and have now acquired good estates in Sugar Plantations and Indigo& co., of course they know no better than what maxims they learn in the Country.

To be now short & plain Your Lordship will see that they have no

maxims of Church and State but what are absolutely anarchical."

In the letter Lawes goes on to complain that these "estated men now are like

Jonah's

gourd" and details the humble origins of the "

creolians"

largely lacking an education and flouting the rules of church and

state. In particular, he cites their refusal to abide by the Deficiency

Act, which required

slave owners to procure from

England one

white person for every 40 enslaved

Africans, thereby hoping to expand their own estates and inhibit further English/

Irish immigration. Lawes describes the government as being "anarchical, but nearest to any form of

Aristocracy".

"Must the King's good subjects at home who are as capable to begin

plantations, as their Fathers, and themselves were, be excluded from

their Liberty of settling Plantations in this noble Island, for ever and

the King and Nation at home be deprived of so much riches, to make a

few upstart

Gentlemen Princes?"

[58]

Anarchy from the Russian Civil War

During the

Russian Civil War - which initially started as a confrontation between the

Communists and

Monarchists - on the territory of today's

Ukraine, a new force emerged, namely the

Anarchist Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine led by

Nestor Makhno. The Ukrainian Anarchist during the Russian Civil War (also called the "Black Army") organized the

Free Territory of Ukraine, an

anarchist society, committed to resisting

state authority, whether

capitalist or

communist.

[59][60] This project was cut short by the consolidation of Bolshevik power. Makhno was described by anarchist theorist

Emma Goldman as "an extraordinary figure" leading a revolutionary peasants' movement.

[61] During 1918, most of Ukraine was controlled by the forces of the

Central Powers,

which were unpopular among the people. In March 1918, the young

anarchist Makhno's forces and allied anarchist and guerrilla groups won

victories against German, Austrian, and Ukrainian nationalist (the army

of

Symon Petlura) forces, and units of the

White Army,

capturing a lot of German and Austro-Hungarian arms. These victories

over much larger enemy forces established Makhno's reputation as a

military tactician; he became known as

Batko (‘Father’) to his admirers.

[62]

At this point, the emphasis on military campaigns that Makhno had

adopted in the previous year shifted to political concerns. The first

Congress of the Confederation of Anarchists Groups, under the name of

Nabat

("the Alarm Drum"), issued five main principles: rejection of all

political parties, rejection of all forms of dictatorships (including

the

dictatorship of the proletariat,

viewed by Makhnovists and many anarchists of the day as a term

synonymous with the dictatorship of the Bolshevik communist party),

negation of any concept of a central state, rejection of a so-called

"transitional period" necessitating a temporary dictatorship of the

proletariat, and self-management of all workers through free local

workers' councils

(soviets). While the Bolsheviks argued that their concept of

dictatorship of the proletariat meant precisely "rule by workers'

councils", the Makhnovist platform opposed the "temporary" Bolshevik

measure of "party dictatorship". The

Nabat was by no means a puppet of Mahkno and his supporters, from time to time criticizing the Black Army and its conduct in the war.

In 1918, after recruiting large numbers of Ukrainian peasants, as well as numbers of Jews, anarchists,

naletchki, and recruits arriving from other countries, Makhno formed the

Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine,

otherwise known as the Anarchist Black Army. At its formation, the

Black Army consisted of about 15,000 armed troops, including infantry

and cavalry (both regular and irregular) brigades; artillery detachments

were incorporated into each regiment. From November 1918 to June 1919,

using the Black Army to secure its hold on power, the Makhnovists

attempted to create an anarchist society in Ukraine, administered at the

local level by autonomous peasants' and workers' councils.

The agricultural part of these villages was composed of peasants,

someone understood at the same time peasants and workers. They were

founded first of all on equality and solidarity of his members. All, men

and women, worked together with a perfect conscience that they should

work on fields or that they should be used in housework... Working

program was established in meetings where all participated. They knew

then exactly what they had to make.

—Makhno, Russian Revolution in Ukraine

New relationships and values were generated by this new social

paradigm, which led Makhnovists to formalize the policy of free

communities as the highest form of

social justice. Education was organized on

Francisco Ferrer's

principles, and the economy was based upon free exchange between rural

and urban communities, from crop and cattle to manufactured products,

according to the science proposed by

Peter Kropotkin.

[citation needed]

Makhno called the Bolsheviks dictators and opposed the "Cheka [secret

police]... and similar compulsory authoritative and disciplinary

institutions" and called for "[f]reedom of speech, press, assembly,

unions and the like".

[63] The Bolsheviks accused the Makhnovists of imposing a formal government over the

area they controlled,

and also said that Makhnovists used forced conscription, committed

summary executions, and had two military and counter-intelligence

forces: the

Razvedka and the

Kommissiya Protivmakhnovskikh Del (patterned after the

Cheka and the

GRU). However, later historians have dismissed these claims as fraudulent propaganda.

[65]

The Bolsheviks claimed that it would be impossible for a small,

agricultural society to organize into an anarchist society so quickly.

However,

Eastern Ukraine had a large amount of coal mines, and was one of the most industrialised parts of the

Russian Empire.

Spain 1936

In 1919, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), the Spanish

confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions, had grown to 1

million members, and encountered many fights with the police and the

fascists in Spain. On July 18, 1936, General Franco led the army to

launch their fight against the government, but instead of an easy

victory they faced significant obstacles.

[66]

They were met with a big resistance from the people, and the rebels

were supported by military and the police. With the government in

shambles, the workers and peasants took over the government of Spain and

joined together to create a revolutionary militia to fight the

fascists. The workers and peasants were fighting to start a revolution,

not to help save their government. Spain’s society was transposed by a

social revolution. Every business was re-organized to have a company

with no bosses; surprisingly profits increased by over half. While

Stalin wanted to send arms but only on one condition: The party must be

given government positions and the militias be “re-organized.” On May 2,

1937, the CNT issued a warning:

- The guarantee of the revolution is the proletariat in arms. To

attempt to disarm the people is to place oneself on the wrong side of

the barricades. No councillor or police commissioner, no matter who he

is, can order the disarming of the workers, who are fighting fascism

with more self-sacrifice than all the politicians in the rear, whose

incapacity and impotence everybody knows. Do not, on any account, allow

yourselves to be disarmed![66]

On the next day after the warning was issued the CNT’s central

exchange was attacked and the militias prepared to quit, in front of

Barcelona. With this became a power struggle, and confusion which lead

the workers to cease fire and lay down their weapons. The “re-organized”

Republican Army tried one last attempt to gain control, with over

70,000 casualties, and many people fleeing to France, General Franco’s

army entered Barcelona on January 26, 1939 to end the revolution.

[66]

Albania 1997

In 1997, Albania fell into a state of anarchy, mainly due to the

heavy losses of money caused by the collapse of pyramid firms. As a

result of the societal collapse, heavily-armed criminals roamed freely

with near total impunity. There were often 3-4 gangs per city,

especially in the south, where the police did not have sufficient

resources to deal with gang-related crime.

Somalia 1991–2006

Map of Somalia showing the major self-declared states and areas of factional control in 2006.

Following the outbreak of the

civil war in

Somalia

and the ensuing collapse of the central government, residents reverted

to local forms of conflict resolution; either secular, traditional or

Islamic law, with a provision for appeal of all sentences. The legal

structure in the country was thus divided along three lines:

civil law,

religious law and

customary law (

xeer).

[67]

While Somalia's formal judicial system was largely destroyed after the fall of the

Siad Barre regime, it was later gradually rebuilt and administered under different regional governments, such as the autonomous

Puntland and

Somaliland macro-regions. In the case of the

Transitional National Government and its successor the

Transitional Federal Government, new interim judicial structures were formed through various international conferences.

Despite some significant political differences between them, all of

these administrations shared similar legal structures, much of which

were predicated on the judicial systems of previous Somali

administrations. These similarities in civil law included: a) a

charter which affirms the primacy of Muslim

shari'a

or religious law, although in practice shari'a is applied mainly to

matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, and civil issues. The

charter assured the independence of the

judiciary, which in turn was protected by a judicial committee; b) a three-tier judicial system including a

supreme court, a

court of appeals,

and courts of first instance (either divided between district and

regional courts, or a single court per region); and c) the laws of the

civilian government which were in effect prior to the military coup

d'état that saw the Barre regime into power remain in forced until the

laws are amended.

[68]

Lists of ungoverned communities

Ungoverned communities

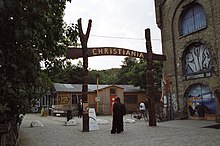

The entrance of

Freetown Christiania, a Danish neighborhood autonomous from local government controls.

- Zomia, Southeast Asian highlands beyond control of governments

- Icelandic Commonwealth (930–1262 CE)

- Ireland for 2000 years prior to Cromwell's invasion[citation needed]

- Republic of Cospaia[citation needed] (1440-1826)

- Anarchy in the United States (17th century)

- The Diggers (England, 1649–1651)

- Libertatia (late 17th century)

- Neutral Moresnet (June 26, 1816 – June 28, 1919)[citation needed]

- Kibbutz, a community movement in Israel initially influenced by anarchist philosophy (Palestine, 1909–1948)

- Kowloon Walled City was a largely ungoverned squatter settlement from the mid 1940s until the early 1970s

- Drop City, the first rural hippie commune (Colorado 1965–1977)

- Comunidad de Población en Resistencia (CPR), indigenous movement (Guatemala, 1988–)

- Slab City, squatted RV desert community (California 1965-)

- The 27 Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities (January 1, 1994 – present)

- Abahlali baseMjondolo, a South African social movement (2005–)

Anarchist communities

Anarchists have been involved in a wide variety of communities. While there are only a few instances of

mass society "anarchies" that have come about from explicitly anarchist revolutions, there are also examples of

intentional communities founded by anarchists.

- Intentional communities

- Mass societies

See also

References

"Decentralism: Where It Came From-Where Is It Going?". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

"anarchy, n.". OED Online. December 2012. Oxford University Press. Accessed January 17, 2013.

Kant, Immanuel (1798). "Grundzüge der Schilderung des Charakters der Menschengattung". In Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht. AA: VII, s.330.

Louden, Robert B., ed. (2006). Kant: Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Cambridge University Press. p. 235.

Malatesta, Errico. "Towards Anarchism". MAN! (Los Angeles: International Group of San Francisco). OCLC 3930443. Agrell, Siri (2007-05-14). "Working for The Man". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2008-04-14. "Anarchism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-29. "Anarchism". The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: 14. 2005. Anarchism is the view that a society without the state, or government, is both possible and desirable.

The following sources cite anarchism as a political philosophy: Mclaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 59. ISBN 0-7546-6196-2. Johnston, R. (2000). The Dictionary of Human Geography. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 0-631-20561-6.

Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003.

"The IAF - IFA fights for : the abolition of all forms of authority whether economical, political, social, religious, cultural or sexual.""Principles of The International of Anarchist Federations"

"Anarchism,

then, really stands for the liberation of the human mind from the

dominion of religion; the liberation of the human body from the dominion

of property; liberation from the shackles and restraint of government.

Anarchism stands for a social order based on the free grouping of

individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth; an order

that will guarantee to every human being free access to the earth and

full enjoyment of the necessities of life, according to individual

desires, tastes, and inclinations." Emma Goldman. "What it Really Stands for Anarchy" in Anarchism and Other Essays.

Individualist

anarchist Benjamin Tucker defined anarchism as opposition to authority

as follows "They found that they must turn either to the right or to the

left, — follow either the path of Authority or the path of Liberty.

Marx went one way; Warren and Proudhon the other. Thus were born State

Socialism and Anarchism... Authority, takes many shapes, but, broadly

speaking, her enemies divide themselves into three classes: first, those

who abhor her both as a means and as an end of progress, opposing her

openly, avowedly, sincerely, consistently, universally; second, those

who profess to believe in her as a means of progress, but who accept her

only so far as they think she will subserve their own selfish

interests, denying her and her blessings to the rest of the world;

third, those who distrust her as a means of progress, believing in her

only as an end to be obtained by first trampling upon, violating, and

outraging her. These three phases of opposition to Liberty are met in

almost every sphere of thought and human activity. Good representatives

of the first are seen in the Catholic Church and the Russian autocracy;

of the second, in the Protestant Church and the Manchester school of

politics and political economy; of the third, in the atheism of Gambetta

and the socialism of Karl Marx." Benjamin Tucker. Individual Liberty.

Ward, Colin (1966). "Anarchism as a Theory of Organization". Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

Anarchist historian George Woodcock report of Mikhail Bakunin's

anti-authoritarianism and shows opposition to both state and non-state

forms of authority as follows: "All anarchists deny authority; many of

them fight against it." (pg. 9)...Bakunin did not convert the League's

central committee to his full program, but he did persuade them to

accept a remarkably radical recommendation to the Berne Congress of

September 1868, demanding economic equality and implicitly attacking

authority in both Church and State."

Brown, L. Susan (2002). "Anarchism as a Political Philosophy of Existential Individualism: Implications for Feminism". The Politics of Individualism: Liberalism, Liberal Feminism and Anarchism. Black Rose Books Ltd. Publishing. p. 106.

"That

is why Anarchy, when it works to destroy authority in all its aspects,

when it demands the abrogation of laws and the abolition of the

mechanism that serves to impose them, when it refuses all hierarchical

organization and preaches free agreement — at the same time strives to

maintain and enlarge the precious kernel of social customs without which

no human or animal society can exist." Peter Kropotkin. Anarchism: its philosophy and ideal

"anarchists

are opposed to irrational (e.g., illegitimate) authority, in other

words, hierarchy — hierarchy being the institutionalisation of authority

within a society." "B.1 Why are anarchists against authority and hierarchy?" in An Anarchist FAQ

"ANARCHISM,

a social philosophy that rejects authoritarian government and maintains

that voluntary institutions are best suited to express man’s natural

social tendencies." George Woodcock. "Anarchism" at The Encyclopedia of

Philosophy

"In

a society developed on these lines, the voluntary associations which

already now begin to cover all the fields of human activity would take a

still greater extension so as to substitute themselves for the state in

all its functions." Peter Kropotkin. "Anarchism" from the Encyclopaedia Britannica

Sylvan, Richard (1995). "Anarchism". In Goodwin, Robert E. and Pettit. A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy. Philip. Blackwell Publishing. p. 231.

Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 14.

Kropotkin, Peter (2002). Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings. Courier Dover Publications. p. 5. ISBN 0-486-41955-X.R.B. Fowler (1972). "The Anarchist Tradition of Political Thought". Western Political Quarterly (University of Utah) 25 (4): 738–752. doi:10.2307/446800. JSTOR 446800.

Brooks, Frank H. (1994). The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers. p. xi. ISBN 1-56000-132-1. Usually

considered to be an extreme left-wing ideology, anarchism has always

included a significant strain of radical individualism, from the

hyperrationalism of Godwin, to the egoism of Stirner, to the

libertarians and anarcho-capitalists of today

Joseph

Kahn (2000). "Anarchism, the Creed That Won't Stay Dead; The Spread of

World Capitalism Resurrects a Long-Dormant Movement". The New York Times (5 August).Colin Moynihan (2007). "Book Fair Unites Anarchists. In Spirit, Anyway". New York Times (16 April).

Tormey, Simon (2004). Anti-Capitalism, A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications. pp. 118–119.

Post-left anarcho-communist Bob Black after analysing insurrectionary anarcho-communist Luigi Galleani's view on anarcho-communism went as far as saying that "communism is the final fulfillment of individualism....

The apparent contradiction between individualism and communism rests on

a misunderstanding of both.... Subjectivity is also objective: the

individual really is subjective. It is nonsense to speak of

'emphatically prioritizing the social over the individual'.... You may

as well speak of prioritizing the chicken over the egg. Anarchy is a

'method of individualization'. It aims to combine the greatest

individual development with the greatest communal unity."Bob Black. Nightmares of Reason.

"Modern

Communists are more individualistic than Stirner. To them, not merely

religion, morality, family and State are spooks, but property also is no

more than a spook, in whose name the individual is enslaved - and how

enslaved!...Communism thus creates a basis for the liberty and Eigenheit

of the individual. I am a Communist because I am an Individualist.

Fully as heartily the Communists concur with Stirner when he puts the

word take in place of demand - that leads to the dissolution of

property, to expropriation. Individualism and Communism go hand in

hand." Max Baginski. "Stirner: The Ego and His Own" on Mother Earth. Vol. 2. No. 3 MAY, 1907

"This stance puts him squarely in the libertarian socialist tradition and, unsurprisingly, (Benjamin) Tucker referred to himself many times as a socialist and considered his philosophy to be "Anarchistic socialism." "An Anarchist FAQby Various Authors

"Because

revolution is the fire of our will and a need of our solitary minds; it

is an obligation of the libertarian aristocracy. To create new ethical

values. To create new aesthetic values. To communalize material wealth.

To individualize spiritual wealth." Renzo Novatore. Toward the Creative Nothing

Skirda, Alexandre. Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968. AK Press, 2002, p. 191.

Catalan historian Xavier Diez reports that the Spanish individualist anarchist press was widely read by members of anarcho-communist groups and by members of the anarcho-syndicalist trade union CNT. There were also the cases of prominent individualist anarchists such as Federico Urales and Miguel Gimenez Igualada who were members of the CNT and J. Elizalde who was a founding member and first secretary of the Iberian Anarchist Federation. Xavier Diez. El anarquismo individualista en España: 1923-1938. ISBN 978-84-96044-87-6

Within the synthesist anarchist organization, the Fédération Anarchiste,

there existed an individualist anarchist tendency alongside

anarcho-communist and anarchosyndicalist currents. Individualist

anarchists participating inside the Fédération Anarchiste included Charles-Auguste Bontemps, Georges Vincey and André Arru. "Pensée et action des anarchistes en France : 1950-1970" by Cédric GUÉRIN

In Italy in 1945, during the Founding Congress of the Italian Anarchist Federation, there was a group of individualist anarchists led by Cesare Zaccaria who was an important anarchist of the time.Cesare Zaccaria (19 August 1897-October 1961) by Pier Carlo Masini and Paul Sharkey

""Resiting the Nation State, the pacifist and anarchist tradition" by Geoffrey Ostergaard". Ppu.org.uk. 1945-08-06. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

George Woodcock. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962)

Fowler, R.B. "The Anarchist Tradition of Political Thought." The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4. (December 1972), pp. 743–744.

Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-900384-89-1.

Daniel Guérin. Anarchism: From Theory to Practice.

"At the end of the century in France, Sebastien Faure took up a word

originated in 1858 by one Joseph Déjacque to make it the title of a

journal, Le Libertaire. Today the terms 'anarchist' and 'libertarian'

have become interchangeable."

Perlin, Terry M. (1979). Contemporary Anarchism. Transaction Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 0-87855-097-6.

Noam Chomsky, Carlos Peregrín Otero (2004). Language and Politics. AK Press. p. 739.

Morris, Christopher (1992). An Essay on the Modern State. Cambridge University Press. p. 61.

(Using "libertarian anarchism" synonymously with "individualist

anarchism" when referring to individualist anarchism that supports a market society).

Burton, Daniel C. Libertarian anarchism (PDF). Libertarian Alliance.

- Ward, Colin. Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press 2004 p. 62

- Goodway, David. Anarchists Seed Beneath the Snow. Liverpool Press. 2006, p. 4

- MacDonald, Dwight & Wreszin, Michael. Interviews with Dwight Macdonald. University Press of Mississippi, 2003. p. 82

- Bufe, Charles. The Heretic's Handbook of Quotations. See Sharp Press, 1992. p. iv

- Gay, Kathlyn. Encyclopedia of Political Anarchy. ABC-CLIO / University of Michigan, 2006, p. 126

- Woodcock, George.

Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Broadview

Press, 2004. (Uses the terms interchangeably, such as on page 10)

- Skirda, Alexandre. Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968. AK Press 2002. p. 183.

- Fernandez, Frank. Cuban Anarchism. The History of a Movement. See Sharp Press, 2001, page 9.

Graeber, David (2004). Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (PDF). Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. ISBN 0-9728196-4-9.

Sahlins, Marshall (2003). Stone Age Economics. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32010-0.

Steven Pinker's The Blank Slate, pages 330-331.

"Seven Lies About Civilization, Ran Prieur". Greenanarchy.org. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Industrial Society and Its Future, Theodore Kaczynski

Zerzan, John (2002). Running on Emptiness: The Pathology of Civilization. Feral House. ISBN 0-922915-75-X.

Zerzan, John (1994). Future Primitive: And Other Essays. Autonomedia. ISBN 1-57027-000-7.

Industrial Society and Its Future, Theodore Kaczynski

Freud, Sigmund (2005). Civilization and Its Discontents. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-05995-2.

Shepard, Paul (1996). Traces of an Omnivore. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-431-6.

"The Consequences of Domestication and Sedentism by Emily Schultz, et al". Primitivism.com. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Clastres, Pierre (1994). Archeology of a kind of Violence. Semiotext(e). ISBN 0-936756-95-0.

"The Putney Debates, The Forum at the Online Library of Liberty".

Source: Sir William Clarke, Puritanism and Liberty, being the Army

Debates (1647-9) from the Clarke Manuscripts with Supplementary

Documents, selected and edited with an Introduction A.S.P. Woodhouse,

foreword by A.D. Lindsay (University of Chicago Press, 1951).]

"Chapter XIII". Oregonstate.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Thomas Carlyle. The French Revolution.

"Duke d'Aiguillon". Justice.gc.ca. 2007-11-14. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

"Revolution in Search of Authority". Victorianweb.org. 2001-10-26. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Jamaica: Description of the Principal Persons there (about 1720, Sir Nicholas Lawes, Governor) in Caribbeana Vol. III (1911), edited by Vere Langford Oliver

Yekelchyk 2007, p 80.

Charles Townshend, John Bourne, Jeremy Black (1997). The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820427-2.

Emma Goldman (2003). My Disillusionment in Russia. Courier Dover Publications. p. 61. ISBN 0-486-43270-X.

Edward R. Kantowicz (1999). The Rage of Nations. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 0-8028-4455-3.

Declaration Of The Revolutionary Insurgent Army Of The Ukraine (Makhnovist). Peter Arshinov, History of the Makhnovist Movement (1918-1921), 1923. Black & Red, 1974

Guerin, Daniel. Anarchism: Theory and Practice

"Spain's Revolutionary Anarchist Movement". Flag.blackened.net. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Central Intelligence Agency (2011). "Somalia". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

External links

The dictionary definition of anarchy at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of anarchy at Wiktionary- Emma Goldman, Anarchism and Other Essays

- On the Steppes of Central Asia, by Matt Stone. Online version of book, hosted by Anarchism.net.

- Who Needs Government? Pirates, Collapsed States, and the Possibility of Anarchy, August 2007 issue of Cato Unbound focusing on Somali anarchy.

- "Historical Examples of Anarchy without Chaos", a list of essays hosted by royhalliday.home.mingspring.com.

- "www.anarchyisorder.org, online @n@rchive" Principles, propositions & discussions for Land and Freedom

- Brandon's Anarchy Page, classic essays and modern discussions. Online since 1994.

- Humanity Surprised It Still Hasn’t Figured Out A Better Alternative To Letting Power-Hungry Assholes Decide Everything (2014-06-25), The Onion

- Anarchism Collection From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress